The Beta-Binomial model

One of the hot topics of these days is the record of retracted scientific papers in 2023, as reported by Nature in this article. Even Nature Journal itself had 7 retractions out of 4320 published articles. I wanted to have an estimate about what’s the probability that after submitting an article to that Journal, the article gets retracted. Let us assume that the retraction probability will be roughly constant in the near future. This is of course quite a strong assumptions, as it is likely that the journal will take some measure to reduce the retraction ratio in the future, but this is just a working assumption, since otherwise we should model how the measures will affect the retraction probability, and modelling an unknown trend would introduce additional arbitrariness in our model. We decide that it’s better to stick to the simpler assumption, so that it will be easier to control the sources of error.

The frequentist way

Let us start by doing the calculation in the frequentist way. First of all, we assume that each article is retracted with the same probability $\theta \in [0, 1]\,.$ This implies that the total number of retracted articles $Y$ out of $n$ published articles is distributed as

\[Y \sim \mathcal{Binom}(\theta, n)\]The binomial distribution

In other terms, we assume that we are looking for the best distribution within the family

\[\{p(k \vert \theta, n) = \binom{n}{k} \theta^k (1-\theta)^{n-k}\}_\theta\]There is more than one possible criteria to decide which is the best parameter $\theta\,.$

The Maximum likelihood method

This method looks for the parameter $\theta$ such that the likelihood for the observed data is maximum for any allowed value for $\theta$:

\[\bar\theta : p(x \vert \bar\theta) > p(x \vert \theta)\, \forall\, \theta \in \mathcal{D}\]where $\mathcal{D}$ is the domain we are looking for. For the binomial model, since the parameter space is continuous, we can simply require

\[\frac{d}{d\theta} \binom{n}{y} \theta^k (1-\theta)^{n-y} = 0\,.\]Since the probability mass function is positive for any $\theta$ within our domain, we can safely take the logarithm of the likelihood and work with the so-called log-likelihood.

\[\frac{d}{d\theta}\log\left( \binom{n}{y} \theta^k (1-\theta)^{n-y}\right) _\bar{\theta}= 0\,.\]By computing the derivative, we get

\[\frac{y}{\bar\theta} - \frac{n-y}{1-\bar\theta} = 0\]and this can be easily solved obtaining

\[\bar\theta = \frac{y}{n}\,.\]You can easily verify that it is a maximum, since the second derivative reads

\[\frac{d^2}{d\theta^2}\log\left( \binom{n}{y} \theta^k (1-\theta)^{n-y}\right) _{\theta=\bar{\theta}=y/n} = -\frac{1}{\bar{\theta}(1-\bar{\theta})}<0 \, if\, 0<y<n\]The method of moments

This method matches the moments of the distribution with the observed corresponding statistics. In our case we can simply match \(\mathbb{E}[y]\) with the observed number of successes:

\[y = n \bar\theta\]and, in our case, this is equivalent to the MLE.

Estimating the confidence interval

We can also obtain a confidence interval for $\theta\,,$ but in order to do so we must rely on the central limit theorem, which tells us that the

\[\frac{Y -n \bar{\theta}}{\sqrt{n \bar\theta (1-\bar\theta)}} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, 1)\]In order to get the $1-\alpha$ CI we only have to evaluate the CI with a significance $\alpha$ for the normal distribution with zero mean and unit variance. Since the distribution is symmetric around 0, the CI is

\[[z_{\alpha/2}, z_{1-\alpha/2}] = [-z_{1-\alpha/2}, z_{1-\alpha/2}]\,,\]as we are leaving outside from the CI a region with probability $\alpha\,,$ so we must leave out $\alpha/2$ on the lower side and $\alpha/2$ on the upper side. We will stick for now to the usual $\alpha=0.05\,,$ so $z_{0.975}=1.96\,,$ and our confidence interval reads

\[[ \bar{\theta} -z_{1-\alpha/2} \sqrt{\frac{\bar{\theta}(1-\bar{\theta})}{n}}, \bar{\theta} +z_{1-\alpha/2} \sqrt{\frac{\bar{\theta}(1-\bar{\theta})}{n}} ]d =[0.4 \, 10^{-3}, 2.8\, 10^{-3}]\]We stress again that this does not represent the range where $\theta$ is within $1-\alpha$ probability, as $\theta$ is not a random variable. What we know is that, if we repeat the experiment many times and every time we construct a CI with significance $\alpha\,,$ then a fraction $1-\alpha$ of the CI will contain the true value $\theta\,.$

The Bayesian way

Also in this case, we assume that

\[Y \sim \mathcal{Binom}(\theta, n)\]where $n$ is fixed. We must now specify a prior distribution for $\theta\,,$ with the requirement that it must have $[0, 1]$ as support. A flexible enough family of distributions is given by the Beta distribution \(\mathcal{Beta}(\alpha, \beta)\,.\)

The beta distribution

The beta distribution is defined via $$ p(x | \alpha, \beta) \propto x^{\alpha-1} (1-x)^{\beta-1}\,,x\in[0, 1] $$ The probability density function $p(x|\alpha, \beta)$ must be integrable, we therefore have $\alpha,\beta > 0\,.$ This distribution takes its name from the normalization constant, which is the inverse of the Euler beta function $$ B(\alpha, \beta) = \int_0^1 dx x^{\alpha-1}(1-x)^{\beta-1} $$ $$ p(x | \alpha, \beta) = \frac{1}{B(\alpha, \beta)} x^{\alpha-1} (1-x)^{\beta-1} $$ The expected value for a random variable distributed according to the beta distribution is $$ \begin{align} \mathbb{E}[X] = & \frac{1}{B(\alpha, \beta)} \int_0^1 dx x x^{\alpha-1} (1-x)^{\beta-1} = \frac{B(\alpha+1, \beta)}{B(\alpha, \beta)} = \frac{\Gamma(\alpha+1)\Gamma(\beta)}{\Gamma(\alpha+\beta+1)} \frac{\Gamma(\alpha+\beta)}{\Gamma(\alpha)\Gamma(\beta)} = \frac{\alpha}{\alpha+\beta} \end{align} $$ In a similar way one obtains $$ Var[X] = \frac{\alpha \beta}{(\alpha+\beta)^2(\alpha+\beta+1)} $$

Now the question is: which values for $\alpha$ and $\beta$ should we choose should we choose? This is one of the central issues in Bayesian statistics, and there are many ongoing debates on this. A possible choice would be to choose $\alpha=\beta=1\,,$ and in this way we would reduce our distribution to the uniform distribution \(\mathcal{U}(0, 1)\,.\) This makes sense, as we don’t want to put too much information in our prior. If this is our aim, an even better choice is the Jeffreys prior for the Binomial distribution, which corresponds to \(\alpha = \beta = 1/2\,.\) Roughly speaking, this is equivalent to the requirement that locally there is the least information as possible. We can now build our model as

\[\begin{align} \theta & \sim \mathcal{Beta}(1/2, 1/2) \\ Y & \sim \mathcal{Binom}(\theta, n) \end{align}\]An analytic treatment would be possible, but we prefer to show how to use python in order to solve this problem.

# Let us first import the libraries

import numpy as np

import pymc as pm

import arviz as az

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

# The data

k = 7

n = 4320

# For reproducibility

rng = np.random.default_rng(42)

# The model

with pm.Model() as betabin:

theta = pm.Beta('theta', alpha=1/2, beta=1/2)

y = pm.Binomial('y', p=theta, n=n, observed=k)

In this way, the model is specified. We can now perform the sampling (or, in jargon, compute the traces)

with betabin:

trace = pm.sample(random_seed=42)

All the sampled data is available inside the trace object. We can visually inspect the traces as

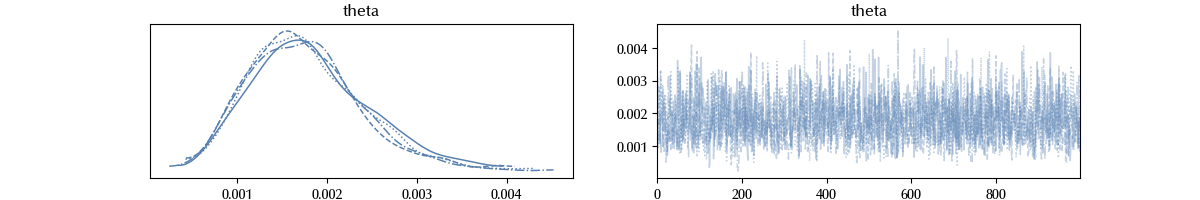

az.plot_trace(trace)

The trace looks fine. For the moment trust me, we will discuss later in this blog how to verify if the sampling had problems.

We can also get some useful information like the mean or the standard variance, together with some estimate of the error.

az.summary(trace)

| mean | sd | hdi_3% | hdi_97% | mcse_mean | mcse_sd | ess_bulk | ess_tail | r_hat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| theta | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0 | 0 | 1843 | 2118 | 1 |

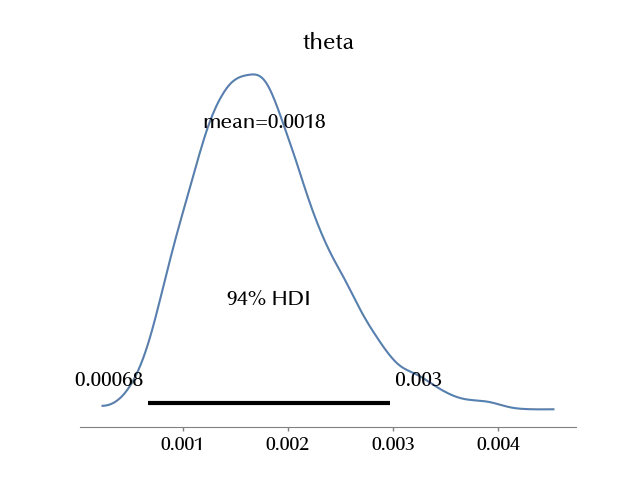

In the above table “hdi” corresponds to the Highest Density Interval (HDI), and it is the central interval which contains the specified probability, so we may say that with probability $0.94$ the parameter $\theta$ is inside $[0.001, 0.003]\,.$ The remaining statistics (MCSE, ESS and $\hat{R}$) will be discussed in a future post.

We can also plot the posterior distribution for $\theta$

az.plot_posterior(trace)

Comparing the results

As we have seen, the frequentist confidence interval for our estimate is \([0.4 \, 10^{-3}, 2.8\, 10^{-3}]\) which is very close to the Bayesian credible interval, namely \([0.001, 0.003]\,.\) The reason for this is that, for a large class of well definite models with a finite number of parameters, when the sample size grows, the Bayesian credible interval approaches the frequentist confidence interval, and this result is known as the Bernstein-von Mises theorem.

There have been proposed many methods for computing the confidence interval in the small sample limit, such as the Wilson confidence interval or the Clopper-Pearson confidence interval, but they are often hard to implement and to explain than the method used above. Due to these difficulties, it is generally recommended to use the central limit theorem to estimate confidence intervals.

We therefore have that we can only use the central limit theorem to compute the confidence interval when the sample size is large, while we can always compute the credible interval. We also have that, when the sample size is large enough, we can approximate the confidence interval with the credible interval.

For this reason, we see no reason not to stick to the Bayesian framework rather limiting ourselves to large samples and getting similar results.

Conclusions

We estimated the retraction probability on Nature Journal both in the frequentist way and in the Bayesian one by using PyMC in the latter case. We showed that the Bayesian approach allows for a simpler interpretation of the results. Moreover, reporting the full posterior provides much more information about how the data constrain the parameter. We also introduced two key issues in the Bayesian approach, the prior specification and the assessment of the sample convergence.

%load_ext watermark

%watermark -n -u -v -iv -w

Python implementation: CPython

Python version : 3.12.7

IPython version : 8.24.0

numpy : 1.26.4

matplotlib: 3.9.2

pymc : 5.17.0

arviz : 0.20.0

Watermark: 2.4.3

Suggested readings

- Gelman, A., Carlin, J. B., Stern, H. S., Rubin, D. B. (2003). Bayesian Data Analysis, Second Edition. US: Taylor & Francis.