Causal inference and Bayesian networks

In the last section we discussed how to ensure, from a theoretical point of view, that association implies causation. We stress that we are talking about the theoretical point of view because, from a practical perspective, only domain knowledge can ensure us that theory matches with reality.

In this post we will discuss a set of tools which might be helpful when discussing causal relations, namely Directed Acyclic Graphs or DAGs. In a DAG we draw, as nodes, all the quantities which might be relevant in the determination of our outcome, included the outcome itself, and we draw an arrow whenever one quantity might causally affect another quantity. Therefore, if we draw $A \rightarrow B\,,$ we assume that a change in $A$ would imply a change in $B\,.$ Of course, we always want to keep a probabilistic perspective, we can therefore make the above statement more precise and say that a change in $A$ would imply a change in the probability distribution of $B\,.$ In the case of two events, we might have that the events are disconnected, so $A$ and $B$ are not causally connected, or $A$ causes $B$, or $B$ causes $A\,.$ We assume that events are well located in time, therefore we cannot have cycles. In other words, if $A$ changes $B$ then $B$ cannot change $A\,,$ since the arrow of time goes from $A$ to $B\,.$ We might however have $A_t \rightarrow B_t \rightarrow A_{t+1}\dots\,,$ but this case won’t be discussed here.

A DAG is simply a visual representation of the structure of the joint probability distribution of the relevant quantities.

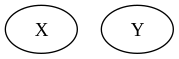

If we only have two disconnected quantities $X$ and $Y\,,$ then

\[p(x, y) = p(x)p(y)\]

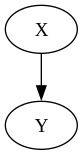

On the other hand in a graph as the one above, we have

\[p(x, y) = p(x) p(y \vert x)\]Let us now consider how might we connect a vertex $X$ to two other vertices $Y$ and $Z$.

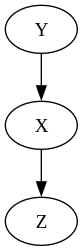

If the $X$ has an incoming arrow and an outgoing one, it is called a chain.

For the chain, we have

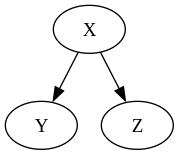

\[p(x, y, z) = p(y) p(x \vert y) p(z \vert x)\]If $X$ has two outgoing arrows, then it is called a fork.

In the case of the fork, the joint probability reads

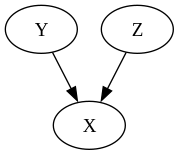

\[p(x, y, z) = p(x) p(y \vert x) p(z \vert x)\]Finally, if it has two incoming arrows, it is called a collider.

In this case

\[p(x, y, z) = p(y) p(z) p(x \vert y, z )\]When does association imply causation?

We can now look for a way to determine when association implies causation.

Let us take a look to what happens when we condition on $x$ in the case of the chain. By using Bayes rule

\[p(y, z \vert x) = \frac{p(x, y, z)}{p(x)} = \frac{p(y) p(x \vert y) p(z \vert x)}{p(x)} =p(y \vert x) p(z \vert x)\]This proves that \(Y \perp\!\!\!\!\perp Z \vert X\,,\) and this implies that there is conditional ignorability between $Y$ and $Z$ given $X\,.$

Analogously, for the fork, we have

\[p(y, z \vert x) = \frac{p(x) p(y \vert x) p(z \vert x)} {p(x)}= p(y \vert x) p(z \vert x)\]and we again got \(Y \perp\!\!\!\!\perp Z \vert X\,.\)

On the other hand, if we have a collider, and we want to ensure that ignorability holds between them, we must integrate out $X\,,$ since

\[p(y, z) = \int dx p(x, y, z) = \int dx p(y) p(z) p(x \vert y, z) = p(y) p(z) \int dx p(x \vert y, z) = p(y) p(z)\,.\]In other terms, if we condition on $X$ and we have a fork or a chain, an association flow implies a causal flow. In the case of colliders, on the other hand, we must not condition on $X\,,$ since doing so would introduce the so-called collider bias. For colliders, if we integrate out $X\,,$ an association between $Y$ and $Z$ implies causality.

To be totally fair, we must say that, even if theoretically the collider bias might be an issue, up to there has never been any evidence1 in any study where this kind of bias have been a true issue, as this bias has always been negligible. However, there is no reason to introduce a possible source of error when this can be avoided, so one should always consider if the collider bias might be a risk. As an example, researchers are afraid about the effect of the collider bias in the risk assessments related to COVID-19, as reported in this article.

The above discussion can be extended to an arbitrary DAG: in order to ensure that association implies causation, we must block all the unblocked (or open) paths, where a path is open if it contains chains or forks. On the other hand, a path is blocked by a collider, and we control for it (or for one of its descendants), we unblock it, and in this way we introduce a bias in our causal estimate. When blocking an open path, we only need to condition on one knot, since conditioning on it is sufficient to identify the flow passing through it. When dealing with a large number of potential causes, this can be a very useful tool to identify a set of minimal quantities we should condition on.

Why is it necessary to block?

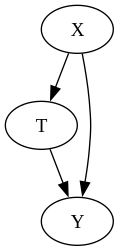

Confounders are variables which might introduce a bias into our estimate, and are those we should control when we want to assess the presence of a causal relationship. Let us clarify why confounders might be an issue.

In an observational study, there might be variables which affect the treatment and/or the outcome. If the variable only affects one of them, this is not an issue at all, since this cannot introduce any bias in the estimate. If however the variable both affects the treatment and the outcome, it means it is a fork, it might introduce a correlation between $T$ and $Y$ even if there is no causal relations between them.

These variables are known as confounders, and they are the main issue in causal inference. As we have seen, we must control for them, but we might not be aware of the existence of such a variable, or we might not know its role in the DAG of the process we are considering.

Therefore, we observational causal studies are always risky, and the presence of unknown confounders is a concrete risk in any observational study. On the other hand, as we have previously seen, in RCTs the treatment cannot depend on $X\,,$ since $T$ is a random variable. This is the main reason why, whenever possible, RCTs are considered the gold standard for study design of any scientific discipline.

A practical perspective

We spent quite a lot of time talking about conditioning, but how can this be done in practical studies? We can condition in many ways:

- for discrete (or discretized2) variables, we can simply provide different results for different values of $X$

- we can use $X$ as a regression variable in our models

- for discrete (or discretized) variables, we can stratify our population on $X$

- we can match on $X$, namely for every individual in the test sample, we look for one or more control individual with the same (or at least a close) value of $X$. Matching has important drawbacks too. In particular, once you match, you cannot unmatch. This means that you cannot think about the test and the control samples, but only about the test and control individuals, since the control individuals cannot be considered as randomly taken from any population. Moreover, if the dimensionality of $X$ grows, it might become difficult to find an appropriate control individual.

- we can restrict our study to a particular value of $X\,.$

Bradford-Hill criteria

In 1965 Austin Bradford-Hill, a statistician and epidemiologist who first established the causal relationship between smoke and cancer, formulated a list of criteria which are often helpful in assessing the presence of a causal relationship. As explained in this article, these are:

- Strength: usually strong correlations are less likely originated from chance or bias.

- Consistency: if the relationship appears in different experiments performed in different setup and with different methodologies, it is more likely that there is a causal relationship.

- Specificity: the causal relationship is more likely when both the population and the effect is well-defined.

- Temporality: obviously, the effect should always come after the cause.

- Dose-response gradient: if the effect increases when the exposure to the cause is increased, then a causal relationship is more likely. This is not always the case, as there might be some threshold effect.

- Plausibility: the relationship should be soundy. Of course, it might always be the case that the relationship cannot be explained within the current knowledge, but in most cases this is not true.

- Coherence: the causal interpretation should not seriously conflict with the known domain knowledge.

- Experiment: causal relationship coming from reliable experimental setup, preferably RCTs, are more likely to be true.

Conclusions

Causal inference is a very hard topic, and before claiming a causal relationship one should be able to exclude any other interpretation for the observed correlation and systematically reproduce the effect. DAG formalism might be helpful in clarifying the possible relations within the relevant variables, but one should keep in mind that unknown confounders might be always present and relevant.