The problem solving workflow

Model building is just a tiny part of statistics, which is itself just one of the disciplines belonging to data science.

Here we will try and make one step back, and see how we could improve the reliability of our results by carefully thinking at our entire workflow.

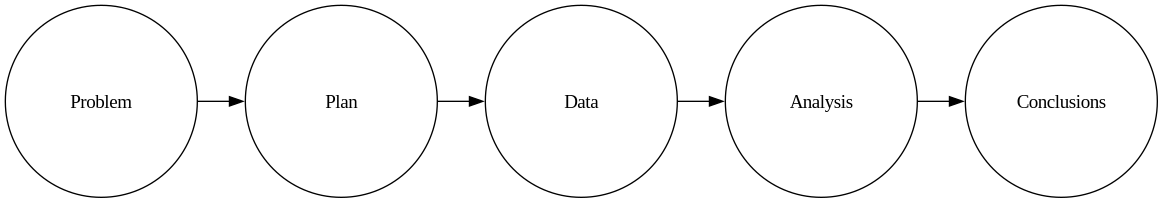

The PPDAC cycle

Both in academia and in industry, we don’t build models for the sake of fun1, but we do so in order to solve a problem. In order to improve our workflow, it is useful to model it, and the representation which better fits my needs is the PPDAC workflow, also named PPDAC cycle2, which is made up by 5 steps:

- Problem

- Plan

- Data

- Analysis

- Conclusions

This workflow is extensively discussed in Spiegelhalter’s book, and here we will only briefly summarize the main concepts.

Each step is preparatory to the next one, and the better we perform each step, the easier will be for us to perform the rest of the workflow.

Step 1: Problem

We generally start with a problem, and this can be either a business problem or a research question. This is usually a rather abstract question, and we should rephrase it in the most precise way we can, since it will be the core of the entire workflow, and all the decisions we will take will be driven by this question.

The question might be any kind, and you might want to falsify a hypothesis, to have a better estimate of some relevant parameter, or maybe to find the optimal setup for a process you are using. Alternatively, you might only have a vague idea about the topic, and in this case an exploratory data analysis together with a review of the literature would be appropriate.

We should clearly define our target population and therefore which are the units of our study. Another choice to be done is which are the variables we should consider, those we can change and those which we cannot control, but we can measure. Moreover, we have to consider which are the nuisance factors, which are the variables we can neither measure nor control, but that might affect our outcome. We can distinguish between four types of variables:

- the outcome variables, which we generally denote with the letter $y$, and are the variables of interest.

- the treatment variables, which are the variables we can tune at (or at least close to) the desired value.

- the blocking variables, which are the ones we cannot change, but we can measure.

- the nuisance (or lurking) variables, which are the ones we cannot (easily) measure nor set to a desired level.

We should also decide what kind of analysis we will perform. Do we have a clear hypothesis in mind? Or do we simply want to take a look at the data and clarify our ideas? Or maybe we already have a model, and we decide that we want to have a better estimate of one or more of the parameters of the model. Or we maybe need to find out which is the best value of some quantity we must choose. These four questions are very different among each other, and each of them requires a separate workflow and its own kind of models. While in the first case we might consider using a confirmatory analysis, leading us to use methods such as A/B testing, in the second case an exploratory analysis would better fit our needs, and using A/B testing in this case would probably lead us to the wrong conclusions. In the third case we already have a model, so we might seek in the literature for previous estimates to the parameter of interest, and we could use a simulation to decide the amount of data we need to reduce the uncertainties in its estimates up to our needs or even to abandon the problem because we already have an answer. In the last case we are facing an optimization problem, and the data collection plan should account for the presence of possible non-linearity which we could neglect in other kind of problems such as testing.

Step 2: Plan

We should then come out with a plan, and we should always stick to it. This phase is often neglected, and what the plan generally says is “Collect the most data as possible, analyze it and take the conclusions”. This is generally a very bad idea, since this does not tell anything about how to perform the subsequent steps.

The planning phase should generate a statistical analysis plan, so a written document where you clearly state the motivations of the study, the data collection and preprocessing as well as the analysis plan.

In this step we should exactly state how to collect data, how much data to collect, how will you handle missing entries and whatever you will do to preprocess the data… As previously mentioned, if the problem has been clearly defined, we should already have a population in mind, and depending on our question we should choose a sampling strategy. If we need to perform a test, a random sample would be strongly recommended, but if we only need to explore our data, then a random sampling might be not needed and also some found data could be sufficient. If we don’t need to account for interactions or higher order terms in our model, then we might consider collect a certain amount of data. If, on the other hand, higher order terms might be relevant, then much more effort would be needed in the data collection phase.

Simulating the data generating process might help you in the choice of the sample size. In this phase you should also decide if you need to perform a blind or double-blind study, as well as how are you planning to handle the blinding.

In the planning phase, you should not only consider the statistical aspects of your issues, but also all the business-related issues. As an example, these might include legal aspects such as privacy issues ethical issues or data storage aspects. Are you collecting sensible data? Do we need to ask for a privacy permission? Is a simple file sufficient to store all of your data or do you need to set up a database to store it? These are only few examples of the planning problems you might need to consider, and this phase is generally much less trivial than one can imagine.

Step 3: Data

The data collection should be performed, monitored and tracked. In this phase we both collect the data, and we prepare it for the analysis phase. We should record everything we do in this phase. In many cases we might need to discard some data, but the original data should be always available, and in our report we should clearly state why we discarded each entry. By doing so, we will ensure a transparent analysis and our results will be trustable, making easier for anyone else to understand what we did and why we did so. This would also make easier to find out flaws in our data collection and data preparations, making easier to correct our mistakes or plan future studies.

It happens that entire articles have been invalidated in this step, as an example due to an excel misuse, so be sure to record every operation you perform on your data before analyzing it.

There is an entire discipline which tries and define the best practices in this field, namely data quality, and in EU we already have a set of guidelines we should follow.

In the guidelines proposes the FAIR guiding principles, where FAIR is an acronym describing the four guiding principles of the guidelines:

- Findability

- Accessibility

- Interoperability

- Reusability

Step 4: Analysis

Only at this point it comes the analysis, but this phase should only include the execution of the analysis. A good idea is to prepare the analysis software in the planning phase, while the data cleaning steps such as missing value handling should have been performed in the data preprocessing step. A good idea is sometimes to take a small fraction of the data in the planning phase and use it to prepare the software.

Always remember to perform an exploratory data analysis in this step to ensure that your dataset has no issues. Verify that the number of records is consistent with what you expect, that there is no missing subgroup.

You should also always plot your data and provide a summary of the relevant variables.

If needed, consider a blind analysis.

We already discussed more than some model elsewhere in this blog, and we stress again that your analysis process should be appropriate for your business problem. You might not need to use a model at all, or maybe a frequentist approach is better suited to answer your questions.

Step 5: Conclusions

We can finally draw the conclusions, and this is can be really tricky, so you should avoid common logical flaws and only draw conclusions on the basis of the results of the analysis and on your assumptions, which should be clearly stated. You might need to write a report to communicate your conclusions to someone else, either to the decision maker or to your colleagues. This report should include all the relevant steps of your workflow, and should be written in a clear and appropriate language. You should also consider the data visualization principles which we already discussed in this blog in order to clearly communicate what your data says.

The workflow often starts again, since your conclusions will open new questions, so you should start again with a new cycle.

Conclusions

I hope I convinced you that problem-solving is not an easy task. In case I failed, I hope the worlds of Sir Ronald Fisher will convince you.

To consult the statistician after an experiment is finished is often merely to ask him to conduct a post mortem examination. He can perhaps say what the experiment died of.

Sir Ronald Fisher

Suggested readings

- Spiegelhalter, D. (2019). The Art of Statistics: Learning from Data. UK: Penguin Books Limited.