Introduction to Bayesian inference

The main topic of this section will be statistics, and we will mostly discuss Bayesian models.

Why learning Bayesian statistics

Bayesian inference has attracted much interest in recent years, and in the past few decades, many Bayesian models have been developed to tackle various kinds of problems. Most of the modern techniques developed in statistics can be viewed as Bayesian, as reported by Deborah Mayo, philosopher of science and emeritus professor:

It is not far off the mark to say that the majority of statistical applications nowadays are placed under the Bayesian umbrella.

Deborah Mayo

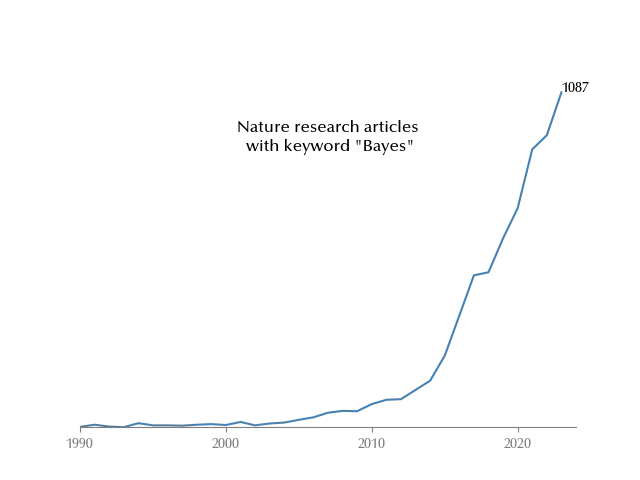

This popularity can be seen by visualizing the number of peer reviewed papers

appearing on Nature tagged as “Bayes”

Bayesian statistics can be a valuable tool for any data scientist, as it easily allows you to build, fit, and criticize any kind of model with minimal effort. In Bayesian inference, you don’t only get an estimate for your parameters; you get the entire probability distribution for them. This means that you can immediately assess the uncertainty for your parameters.

In any statistical model you must specify a likelihood, which represents the probability distribution which generated the data, and we will refer to this quantity as

\[p(x | \theta)\]where $\theta$ represents the unknown parameter vector.

We would like to quantify the uncertainties about the unknown parameters, and the natural way to do so is to estimate their (posterior) probability distribution \(p(\theta | x)\,.\)

In order to do so, we can use Bayes theorem

\[p(\theta | x) = \frac{p(x | \theta)}{p(x)} p(\theta)\]Since the denominator \(p(x)\) is a normalization constant independent on $\theta$ which can be computed by normalizing the left hand side of the equation to 1, its dependence is usually neglected and the Bayes theorem is usually rewritten as

\[p(\theta | x) \propto p(x | \theta) p(\theta)\,.\]We must however provide a prior probability distribution \(p(\theta)\) in order to ensure that \(p(\theta | x)\) can be normalized to one.

While in the past many statisticians interpreted \(p(\theta)\) as the subjective probability distribution for the parameters, nowadays most of the statisticians agree that this object is simply a tool to regularize 1 the integral

\[\int d\theta p(x | \theta) p(\theta)\]since choosing \(p(\theta) = 1\) would make the above integral indefinite. The choice for \(p(\theta)\) should be such that any relevant expectation value

\[\mathbb{E}_\theta[f] = \int d\theta f(\theta) p(x | \theta) p(\theta)\]does only weakly depend on the choice for \(p(\theta)\,.\)

A historical tour in MCMC

While the normalization constant \(p(x)\) can be in principe computed for any model, it can be analytically computed only for a very limited range of models, namely the conjugate models, and for this reason Bayesian models have not been so popular for a long time. However, thanks to the development of Monte Carlo sampling techniques, it became possible to easily sample (pseudo) random numbers according to any probability distribution. These techniques have been developed during the WWII by the Manhattan project group, and it soon became popular among scientists to perform numerical simulations. Up to few years ago, this was however only possible for people with a strong background in numerical techniques, as it was necessary to implement from scratch the sampler. Nowadays things have changed, and Probabilistic Programming Languages such as PyMC, STAN or JAGS allows anyone to implement and fit any kind of model with a minimal effort.

Some philosophical consideration

You may have heard about the war of statistics, which is a debate which lasted almost one century between frequentist statisticians and Bayesian ones. At the beginning of the last century, a group of statisticians tried and promote Bayesian statistics as the only meaningful way to do statistical inference. As previously anticipated, according to them, the prior should have encoded all the available information together with any personal consideration of the researcher. In this way, the posterior probability distribution $p(\theta | x)$ can be interpreted as the updated version of the researcher’s beliefs once the observed data $x$ has been taken into account by a perfectly rational person. This philosophy has been rejected by the majority of the statisticians, as they considered this “subjective” probability meaningless.

Today, however, the prior probability is only considered a regularization tool, which allows you to use Bayes theorem to compute the posterior probability 2. The results should only weakly depend on the prior choice, and this dependence must be taken into account when reporting the fit results. In this way, since the Bernstein–von Mises theorem ensures you that in the long run the Bayesian inference will produce the same results of the model with the same likelihood, one can stick to the usual frequentist interpretation.

Bayesian inference as a tool in the replication crisis

During the beginning of the 2010s, scientists realized that a large part of research articles were impossible to replicate. In these years, many unsound scientific results have been found, and claims such as the existence of paranormal phenomena or that a dead salmon was able to recognize human emotions were not as rare as one would expect 3.

A new research field emerged in these years, namely meta-science (which means the science which studies science), and this produced many proposals to tackle the scientific crisis. One of the issues that came out was that the “golden standard” tool of the 0.05 statistical significance was often misused or misinterpreted, and statisticians suggested that using a broader set of tools to perform statistical analysis would have reduced this problem. As you might imagine, due to the simple interpretation and of the possibility to easily implement structured models and of combining different data sources, Bayesian inference has been popularized by statisticians as one of these tools, and it has gained a lot of attention by the scientific community.

Technical considerations of using Bayesian inference

There are also technical considerations which one should take into account when choosing the analysis method. For simple models there is no reason why one should prefer Bayesian inference to frequentist-based ones, at least as long as the sample size is large enough to allow you using the central limit theorem. However, for complex models, things soon change. One may naively be tempted to simply use the maximum likelihood estimation, which is in principle a valid way to drop out the prior dependence. However, this method relies on finding the extreme of a function, which implies maximizing the derivative of the likelihood. This approach soon becomes unstable as soon as the model complexity grows, and you should spend a lot of effort in ensuring that your numerical approximation is close enough to the true maximum or in looking for some ad-hoc. For these reasons, statistical textbooks devoted to complex models such as longitudinal data analysis models provide many different methods to fit the frequentist models 4.

you must find its zeros, and there is no stable procedure to do so for higher dimensional problems.

The Bayesian method, on the other hand, does not require to compute any derivative, as you simply need to sample the posterior distribution and, as we will see, it is very easy to assess the goodness of such a sampling procedure. If you then want to compute any point estimate \(\mathbb{E}_\theta[f]\), what you have to do is to compute the corresponding expectation value on the sample \(\left\{\theta_i\right\}_i:\)

\[\mathbb{E}_\theta[f] \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N f(\theta_i)\]and, as we will discuss, the estimate of the error associated with this procedure is already implemented in the sampling engine.

Bayesian inference vs Bayesian statistics

There’s a lot of confusion around on what using Bayesian inference means. Let us stress once more that using Bayesian inference does not imply sticking to the subjective interpretation of probability, nor comparing priors to posteriors or anything like that.

We are all frequentist here!5

Andrew Gelman

Using Bayesian inference simply allows you to add structure to your model and being able to directly sample the entire posterior probability of your models.

Problems you will likely face if you use Bayesian inference

There is of course no free lunch, as every method has pros and cons.

First of all, unless you are trained as a statistician, at the beginning you will likely face one problem: the way of thinking. Probabilistic thinking requires a training, but in the long run it will be a priceless tool, as probability is the only consistent way to quantify uncertainties.

From a more practical point of view, the main drawback of using Bayesian methods is that sampling may require time, and while having a high quality sample with few parameters requires seconds, you may need hours or more for a good sample if you are dealing with thousands of parameters.

You should also consider that the prior selection might take require some effort, especially when you are dealing with a new problem or with a new kind of model.

Why do I use Bayesian inference

I always consider using Bayesian inference because it allows me to build, improve and criticize my own models with a minimum effort and some background knowledge. Since the model building process is iterative and modular, it is possible to encode structure in an easy and controlled way, and this is a fundamental requirement for any real world statistical model. These models are 100% transparent, and the fitting procedure is fully transparent too. I can use the same procedure to ensure that I have no numerical issues again and again. Since MCMC samples the entire probability distribution of the model, it is very easy to figure out if there’s any numerical issue. I can then sample the posterior predictive distribution, and this gives me a lot of freedom in deciding how to compare it with the true data, in order to ensure that the model is appropriate for my data. In this way I can focus on the data rather than spending time looking for any pre-built model and looking each time for the options I should fine-tune to improve its performances. I can finally share my results and communicate the uncertainties in a simple way, talking about probability of the parameters rather than making sure that my audience did not misunderstand the concept of confidence interval.

Conclusions

I hope I convinced you that Bayesian inference is a valuable instrument in the toolbox of any data scientist. In the next articles I will show you how to implement, check and discuss Bayesian models in Python. As usual, if you have criticisms or suggestions, feel free to write me.

In this section of the blog we will both discuss Bayesian inference and the Bayesian workflow. I will use Python to perform the computation, and I will use the PyMC ecosystem.

-

By regularizing tool here we mean, as an example, the Tikhonov regularization in the Ridge regression. ↩

-

Here we distinguish between Bayesian inference, which is a set of mathematical tools, and Bayesian inference, which we identify as the subjective interpretation of probability. ↩

-

One is a joke, the other is not. Choosing which one is a joke is left to the reader as an exercise. ↩

-

Even if you analytically compute the derivative, ↩

-

As usual, see Gelman’s blog and references therein. ↩